The Honeyman Festival — 2 May 2024 » 8pm EST

Our 9th meet, and an opportunity to welcome new members.

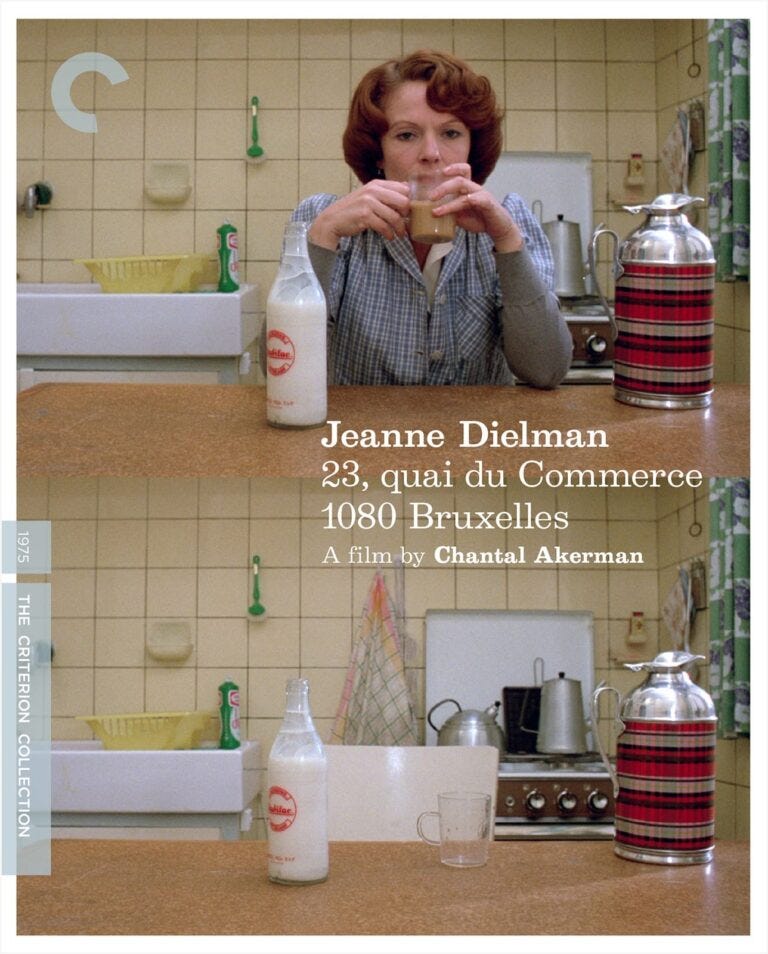

On 2 May, at 8pm EST we will discuss The Honeyman Festival (1970) by Marian Engel ((184 pgs.)) alongside Chantal Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975), named the best film of all-time by the British Film Institute.

We will be hybrid (zoom/in-person) for those who can make it in Montreal. x

Marian Engel, born in 1933, received her MA at McGill, working with John Hugh MacLennan. She died at 51, in 1984, having written seven novels, two collections of short stories, and many essays and articles. She was a founding member of the Writers' Union of Canada, and was also appointed an Officer of the Order of Canada shortly before her death.

Engel was initially going to call the book, The Texture of Women, which makes more sense as a way into what the the novel is about—the ways mothers make sense to each other and themselves.

The Honeyman Festival is also deeply interested in the bond between Minn and her mother, Gertrude Williams. Minn, ultimately, rejects her mother and what she represents.

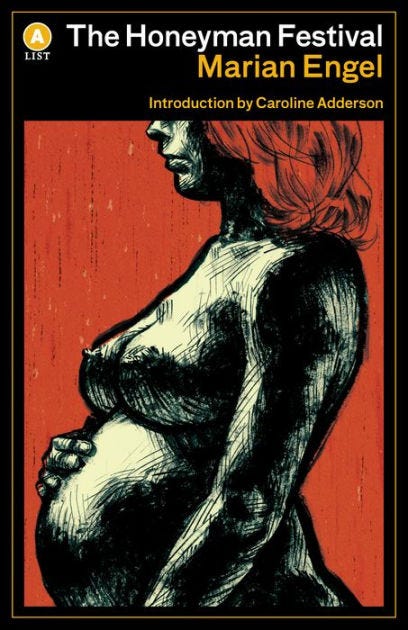

According to Christl Verduyn, the original cover of The Honeyman Festival was “daring for its day.” (and possibly offensive for ours? Curious how people read it.) Engel asked a friend to design it. It showcased a large naked woman with a clock for a head. Her torso, breasts, and belly were exceedingly large, and she was missing hands, feet, a face, and other parts of the body, that allow one’s self to express mobility.

Upon first read, I couldn’t follow Engel’s stream-of-consciousness pace and rhythm which take precedence over a plot. The formal play with which she introduced Minn Burge (the protagonist) and her life in Toronto took time to get used to.

I found this list of “tracks” that Engel wrote in her commentary helpful. Verduyn notes they reveal both the structure and motifs of The Honeyman Festival:

1) Pregnancy

2) Marriage to Norman

3) Motherdom

4) Gertrude

5) Alice (sometimes together)

6) Weeping Willie

7) Godwin Town

8) Rebellion

9) Honeyman - v.subdued

10) hippies & house

During this point in the genocide, it has been difficult to read about lives at a remove from politics. But that shortsightedness left when I started reading the book again in earnest. I recognized the book’s politics in its imagining the unrequited life of a mother that was promised a world outside the confines of the home.

“You’re not for women’s lib, are you, Minn?” She is asked at the party for Honeyman, encircled by a gaggle of “harpies.” She ends the obnoxious conversation with, “I don’t like arguments,” a response that a white woman of a certain class, a child of a former Ontario premier, would have been rewarded for internalizing. Yet, Minn doesn’t fully concede to these rewards, and hints at being queer throughout.

“Minn must show the inadequacies of the Ontario norm,” Engel noted.

Minn's home town of Godwin (Mary Wollstonecraft's husband's name) is teeming with “conservative values and puritan mentality.” Every description of Godwin evokes its repressiveness: “It was said to be closed, snobbish, and polluted” (89), the sort of town where "wherever an arch could be crippled in its clumsy attempt to soar, wherever a window could be darkened or a keystone disproportionately narrowed, it was.” (91).

The Honeyman Festival is an effort to demonstrate the discrepancy between the idealized puritan ethos and female reality.

The novel’s tone, detailed mise-en-scene, exposition through memory, long drawn out conversations, and ennui about being a mother, reminded me of a book published ten years prior, The Torontonians by Phyllis Brett Young (1960), which in detail marked out life for a white woman. Although it lacked Engel’s sensorial and abject wit.

In a letter to Dennis Lee of Anansi House, with whom Engel worked closely to publish The Honeyman Festival, she wrote: "It seems to me there's a lot more gynaecological stuff to be got at but this is probably as much as any general reader can bear." Engel expressed the view that in many ways she did not go far enough towards representing female experience in The Honeyman Festival. She wondered how she could have written an entire novel about motherhood without once mentioning breast feeding. But in 1970 this did not seem so unusual.

This would have been our mothers generation.

Having a party all night long in your house while you are in your 3rd trimseter and your three young children are asleep upstairs?

In Minn’s world, there was no ability to express or even have access to a language with which to express motherhood outside its ideological confines, and when you did,

Mrs N.R. Burge, 37, of 26 Bute Place in the inner core of the city was arrested at 3 p.m. Friday by officers of the Domestic Morality Squad and charged with failing to keep an orderly house….

“Middle-class values have got to be imposed in order to get these girls to clean up,” he said. He designated Mrs Burge’s house as a distressed area … Samples of dirt on upstairs windowpanes were found by Squad inspectors to contain jam, plasticene, Cheez-Whiz, peanut butter and human excrement, and there was a pubic hair in the bathtub. A garbage bag was overturned on the kitchen floor and there was evidence that one child had been eating a mixture which contained honey and hair.

“There’s a pubic hair in the bathtub in Virginia Woolf’s The Years … It’s something that happens as you get older.” She fell into a deep sleep in the back of the police car.

One coping mechanism is humour, and Engel has plenty of it; at times even made me laugh so hard I nearly tinkled.

Engel critiques the white middle-class sensibility in many ways, and particularly with the home Minn has made from their rental house at 26 Bute Place, Toronto: It is drafty and bug-laden, the registers belched soot, the yard was a mud hole of buried glass, the kitchen freezing . . .” In other words, “downright sloppy” is the setting for the novel, and the setting for who Minn feels she has become.

And yet, like she has been taught, the front of the house is elegant. The front of the house is the performance of those white middle-class sensibilites. But the rooms at the back of the house are full of boxes, of things that need space, but the space isn’t made for them, and might never be.

Engel’s descriptions of the house, the mess, the ways in which a mother’s world is always askew, and most often judged by their own mothers, who manage to forget what raising young children is like.

What did people make of the form? Did it remind you in any way of the new generation of plot-less motherhood writing (Manguso, Galchen, etc)?

"What interests me most," Dennis Lee wrote to Marian Engel, "is what you're doing formally. I take it that, at one level, you want these sections to be set-pieces, hopefully tours-de-force which quite unabashedly detach themselves from much of the rest of the book and dance around it in counterpoint. I think this is a neat notion - more than that, that it has in it the seed of a quite marvellous formal ap- proach to some novel.

What does it mean for the literary landscape that "novelists could not resist dead children: Edna O'Brien, Durrell, Dickens, oh, Huxley and Waugh, Joyce even (the stillborn son of Bloom, that was): sweet corpses fell on fiction like leaves."

It is dissapointing, although unsurprising I couldn’t find any recent book reviews of it; as there were many for the original printing. Christl Verduyn details the general oversight of Engel’s work in Lifelines (1995), a feminist literary perspective on Engel and her work, which I quoted throughout my summary here.

Hope these fragments help you appreciate the book.

x

Magda

Thanks for the notes and info! I also had a slow start but it’s growing on me.

The used copy I found has the old original cover. I don’t love it, but I think it’s meant to resemble the “Venus of Willendorf” figurine (an ancient object probably meant to confer fertility). Ah, actually this is written inside + “cover design by Robert Hohnstock.” Looking forward to our conversation.