9th Book Round Up & 10th Book Pick

The 1970s with The Honeyman Festival and the Territory of Light

“I write fiction, but I experience the fiction I write,” Yuko Tsushima wrote in 1989.

Earlier this month we read The Honeyman Festival (1970), our 9th book together.

Meaghan and I/Magda squished next to each other on her studio mate’s sofa, met on Zoom with Emilie, Claudia, Dani, and new member Elizabeth, whom I met at a writing workshop in Toronto, where Art Monsters had our last meeting. Several members were missed, especially as they shared their delight of the book.

To go along with the book, I had chosen Chantal Akerman’s masterpiece, Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975), at the last minute. I wasn’t expecting people to watch it who hadn’t seen it, but it fit so well with the banality of motherhood, that gradually or not so gradually—depending how you experience time—ramps up to detonate.

Our book club had varying opinions on the novel: some were unable to see it through, others sped through it, and some were in-between. The ongoing genocide is always with us, side by side as we grieve and push ourselves to action, making it hard to focus at times. While it may not have been my favorite book to read (which is besides the point anyway), after the meeting, I was grateful to have had a chance to discuss it. In some ways, The Honeyman Festival is a book club book, filling the motherhood lacuna in 1970s literature.

She [Minn] read a lot. They [children] didn’t like you to read, they felt rejected, they pestered, but she went on reading. She locked herself behind the bathroom door and them behind their gate and read for an hour every morning. She read a lot of novels and marvelled at the mass of dead children. Novelists could not resist dead children: Edna O’Brien, Durrell, Dickens, oh, Huxley and Waugh, Joyce even (the stillborn son of Bloom, that was): sweet corpses fell on fiction like leaves.

Several of us remarked that it’s a novel that we would have never read otherwise. Yet, we made time to ruminate on all our ways of entering and staying with, and, leaving the book. It was also great to hear some of us deeply loved the book and what Engel set out to do. The dynamic of what members bring up and how it’s taken up collectively affects our individual read of every book we’ve discussed so far, especially this one; the point of a book club, I suppose.

Specifically, The Honeyman Festival revealed itself more when Emilie clarified Engel’s writing style: its urgency, abstractness, yet minute attention to detail and detritus is what mothers often feel, especially with young children. We are everywhere all at once, and yet often uncertain where to orient. We speak quickly, and sometimes have no words spoken back to us for hours while playing with or observing our babies.

Engel was trying to re-orient the novel beyond plot, and give us the sensorial experiences that mothers are so accustomed to.

to walk into the toweringly shabby house … by the cracked hall window, scowl at the peeling bluebirds on the painted glass, and proceed warily, every inch a lady and bountiful to the core, into the drafty living room where Minn sat swathed in pregnancy and despair, no help, no money, wild raffish children — reaping where she had sown, lying in the bed she had unmade. Minn went down the long steep staircase, caressing the sticky bannister…

She [Minn] wiped the sticky edges of a marble card-table, looped the curtains back from the window and dusted the coffee table with the inside hem of her skirt. She turned into the connecting dining-room and straightened the row of chairs. In the leather well of one of them someone had wet his pants.

Claudia mentioned that Engel was way ahead of her time writing about motherhood in this way, a motherhood that hardly considered the children, and allowed an aloof and ambivalent way of being that most mothers probably had no access to at the time, or rather, had no access to acknowledge.

Indeed, we agreed some of the language is reminiscent of a very white 1970s Toronto, despite the lower class distinction Engel makes.

Elizabeth had made some other astute comments on the form and language I wish I remembered, and also commented that Honeyman was grooming Minn, especially as Minn self-reflected on how affected she was by the periphery of stardom when she was younger.

A main difficulty we had was following the characters, and the ways everyone talked about everyone else. Dani pointed out that she had to go back and forth a few times throughout the novel, especially in the scene with the mother and her aunt, who live together. Many of us did the same. The cast of characters was brimming, unlike Engel’s The Bear, one of Claudia’s favorite books of all time, which she read during her 20s Canlit era.

There was so much more discussed, if you want to share anything outside our email thread, to archive here, please do. Thank you all for being here. xx

Last week, I was listening to the Alice Munro tribute on IDEAS, “The Lives of Women, Readers and Alice Munro” an episode that originally aired in 2017. The episode compiled some of Munro’s interviews with clips from a women’s book club meeting in St. John's, Newfoundland, in which they invited Joan Clark, a friend of Alice Munro, to join them. The women’s reflections sounded very much like us! Making the time to be with a book, to be mothers, women, to be readers with each other. One of the women even joked it should really be called the “didn’t finish the book” club. But I really hope we finish the one coming up…

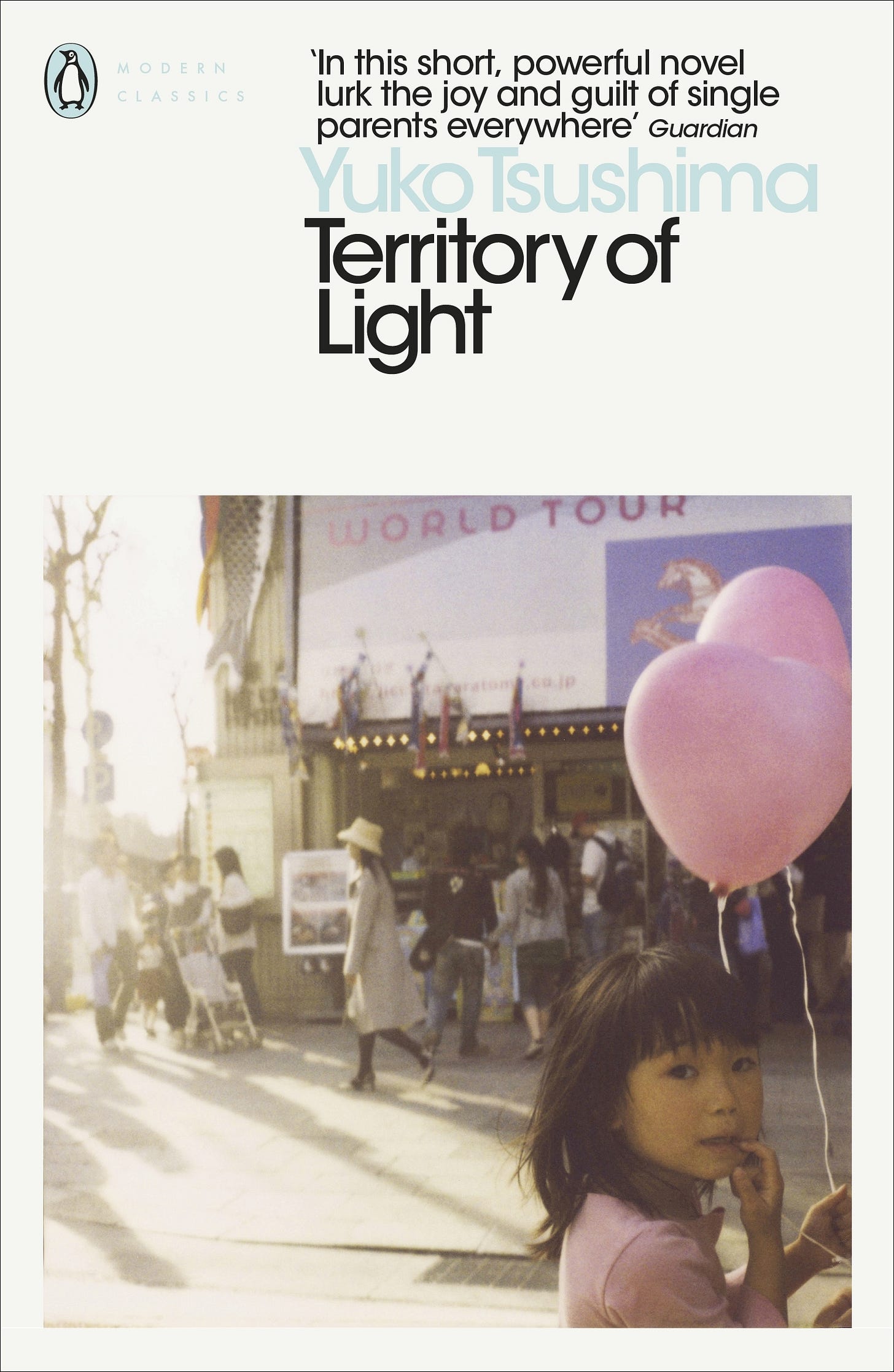

We will meet Monday 17 June 2024 at 8PM EST to discuss another 1970s book— Yuko Tsushima’s autofiction The Territory of Light (2019) with an art work, TBD. Anyone? It is Anabela’s suggestion and the title of her beautiful Substack, in which among other things she writes book reviews that makes me want to read even more than I already do. Email me if you need the e-pub.

Territory of Light (1978-1979/2019) by Yuko Tsushima (122 pgs.)

“Territory of Light was published from 1978 to 1979 as a series of 12 stories in the Japanese literary magazine Gunzō that, once finished, were collected into a novel.”

From a review in the New Yorker:

Dreams and deaths. Can a novel be woven out of such ineffable things?

In “Territory of Light,” Tsushima makes the vaporous seem real, imparting an inner progression to stray signs and portents. Even death comes to exude an earthly “warmth and softness,” and its randomness merges with the randomness of being alive. The narrator is a single mother, recently separated from her husband. She and her two-year-old child move in to a large, well-lit apartment, in Tokyo, on the top floor of a building. We follow them for a year as they figure out how to live on their own. The narrator has dreams that are vivid and ominous. She keeps hearing rumors of acquaintances dying, or running into funerals on her way to work. Her ex-husband is annoyed at being barred from seeing their daughter. Late at night, she is often awakened by the sound of the child crying in her sleep.

For all its apparent desolation, nearly every chapter of the novel culminates in a moment of edifying grace. Whether it’s a pool of water accruing like “the sea” on a rooftop, a brief spell of silence near a traffic intersection at certain hours of the day, or a translated recording of a Goethe lyric that the narrator overhears at her job in the library (“Quick now, give up this idle pondering! / And let’s be off into the great wide world!”), everyday impressions are described with an ardent clarity to make up for the eschewal of plot. It’s a striking formal achievement: the book is held together by the force of its images. But the sentences also draw their delicate vigor from the tension between the novel’s fixation on death and its narrator’s wish to get on with her day—between her father’s passing, as it were, and Goethe’s call to arms.

Still can't find my beloved copy of BEAR 🐻